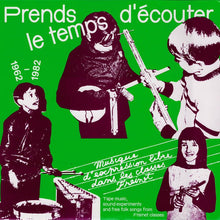

* Prends Le Temps D'écouter - Musique D'expression Libre Dans Les Classes Freinet / Tape Music, Sound Experiments And Free Folk Songs From Freinet Classes - 1962/1982

Born Bad / France / 2023

PRENDS LE TEMPS D’ÉCOUTER

Tape music, sound experiments and free folk songs by children from Freinet classes

1962-1982

France, early sixties: the Mouvement de l’École moderne is in full bloom. Relying on the experiments and writings of its founder, the educationist Célestin Freinet, this consortium of teachers is about to give empirical evidence proving that another approach to music in school can be fruitful, distancing itself from government directives.

With its pragmatic, anti-authoritarian tack, the method that Freinet was already developing in the 1920s held children in respect, giving them confidence and autonomy. In a Europe that was just beginning to recover from WWI, Freinet was working concomitantly with the historical burgeoning of active learning promoted by other great educationists such as Montessori in Italy, Decroly in Belgium or Ferrière in Switzerland, notably within the Ligue international pour l’Éducation nouvelle. Freinet very soon started to put his principles into practice, experimenting in person a series of innovating techniques that would become emblematic: removing the rostrum, reorganizing the classroom, encouraging cooperation, developing activities such as school printing or inter-school correspondence… And all this went with the publishing of documentation, files and specific teaching material by the Coopérative de l’Enseignement Laïc (the CEL, a cooperative for secular education).

A team of inspired associates quickly formed around Célestin and his wife, Élise. Intent on circulating ideas and perfecting methods, they also contributed to structuring a Mouvement that drew increasing attention. When the couple founded its emblematic alternative school in the small town of Vence, in 1934, the CEL was already counting more than three hundred members from sixty different territorial departments. At the dawn of the sixties, the Mouvement gathered a considerable number of teachers working in state schools, and even if they were far from constituting any kind of majority, they could be found throughout the national territory.

As the wish to encourage free expression was central in the Freinet philosophy, arts and crafts were given more importance at school; in this regard, singing and music had a part to play, just as much as writing or drawing. While classrooms filled with a joyful jumble of sound-making objects (springs, bottles and basins, dismantled piano frames, drums, bamboos and the first DIY electronics), singular forms of music started ringing out: wild improvising, delicate a-cappella singing, clanks and dissonant string hammerings, basic experiments with magnetic tapes, evanescent folk songs…

This approach might seem surprisingly ahead of its time, but what is even more astonishing is that physical traces of these experiments can still be accessed today. Between 1962 and 1982, recordings collected from schools everywhere around France were compiled on dozens of vinyl records. Mostly destined to teachers and friends supporting or gravitating around the Mouvement, these short-format records documented the evolution of practices and approaches: catchy headings such as “Musique libre” (free music), “Recherches sur la voix” (vocal experiments), “Musiques concrètes” (concrete music), “Musiques électroniques” (electronic music) or “Musiques d’ailleurs” (music from elsewhere) are particularly telling. And the music that could be heard on these groundbreaking records was the work of pupils from small towns in Lot-et-Garonne, Oise and Alpes Maritime – not exactly the archetypal privileged children benefitting from an upper-class economic and cultural background… Rather, children from rural schools with a single classroom, and sometimes, atypical or struggling children oriented towards the so-called “classes de perfectionnement.”

Free music

Within the Mouvement de l’École moderne, the importance attached to music, its recording and the record itself formed three interrelated topics, the history of which is that of a captivating collective adventure.

When Célestin Freinet sternly declared, during an educational lecture he was giving in 1965, that “the traditional teaching of music had gone bankrupt,” he was actually pointing out that groundwork for an alternative was already in progress. Since the 1930s, the Mouvement’s quest for a “natural method for music initiation” had been adapting the principles of Freinet’s “natural method” for reading skills acquisition. A whole pedagogy grounded in interdisciplinary key notions was imagined, and as always with Freinet, the starting point was practice rather than rule. Dynamic and pragmatic, it encouraged the child’s natural empirical approach, hoping to liberate them from the fear of failure, stimulate their desire for learning and deeply enroot theoretic knowledge in concrete intimate experience. Far from contentedly praising spontaneity, laxness and first drafts, the notion of “enquiry-based learning” claimed equal respect for the various paths that pupils took and considered them able to adopt their own structured approach.

This had many implications for the teaching of arts. The very notion of repertoire gave way to freedom of personal expression as a major value. Instead of trying to have pupils clumsily copy a model, teachers encouraged an intimate experience of production, following Goethe’s maxim according to which children cannot be sensitive to art works unless they have created something themselves. Whether modest or grandiose, the creation was attributed to the child, now considered as an author able to define the intention, the form and the modalities of their work.

In the pre-war issues of L’Éducateur prolétarien, several institutors – sometimes working in close collaboration with Freinet, as Roger Lallemand did – regularly shared their thoughts on the teaching of music at school. Their articles could equally deal with singing as a free practice, the place of pipes or percussion instruments, composition, or the formation and staging of small children orchestras. Clearly aware of the progress that was being made abroad, these contributors also referred to pioneering books and works by the American educationist Satis Coleman or the French one Lina Roth.

When the Institut Coopératif de l’École Moderne (ICEM) was founded in 1947, other teachers and key figures of the Mouvement progressively took the helm. In the second half of the 1950s, Maurice Beaugrand or Paul Delbasty suggested new directions in “free music,” which was then practiced in school as “free writing” or “free drawing” were. In 1957 a special issue of La Bibliothèque de travail directed by Delbasty suggested to begin at the beginning by radically questioning lute-making and the instrumentarium as determining factors in the practice of music and the very form it can take. Taking into account a budgeting that made it difficult for an entire class to be equipped, this issue detailed a whole series of practical solutions to facilitate the building of instruments through recycling: cookware lids, tins of paint, bottles making a xylophone or anything that could be somehow used as a pipe. Cheap and demystified, the instrument was adapted to the height and skills of children: it became both affordable and accessible. A small zither made with a tin of sardines and a bigger one built with a wooden box also heralded the conception of the Ariel, a plucked string instrument that could be easily built and intuitively tuned, and which would become emblematic of the music produced in Freinet classes.

In another BT issue published in 1959, G. Jaegly and C. Pons presented a series of small sound experiments: building other rudimentary instruments, amplifying a vinyl groove with a paper cone, visualising Chladni figures (geometrical patterns that can be observed on a vibrating plate covered with sand). In 1965, in a more theoretical spirit, Freinet and Delbasty drew up a very positive report surveying the work in progress and published it in L’Éducateur, n° 10. Beyond print, these ideas and techniques were promoted through training courses, symposiums and congresses regularly scheduled by the Mouvement.

At the end of the 1960s, research on musical practice began to be carried out, notably, by the “Commission musique,” a group of teachers particularly concerned with these issues. The names of Jean-Pierre Lignon, Paul Le Bohec or Jean-Jacques Charbonnier frequently appeared, along with that of Jean-Louis Maudrin, who coordinated the commission’s work and was one of its major members until 1978:

JLM: We didn’t want everything to be based on music, it was not the goal of the operation. I was interested in offering something to pupils. We wanted children to find out, invent, be included in the teaching process. With productions that were theirs, or others’, never mind. If you want schooling to work, children must be involved, and what can we do to involve them? Music, sculpture, photography… We all intervened in turns, but the goal of the operation was to generate enthusiasm in everyone. And to be honest, it is far from being a piece of cake, because you have to do with what you get. If you want to make instruments, is there enough room for construction anywhere in the class? It was a recurrent problem, especially in big city schools.

Respecting the autonomy, creativity and rhythm of each child, activities were also systematically envisaged as something to be shared with the whole class and penfriends in distant schools, to whom recordings were sent.

JLM: Sometimes the class was totally split up, sometimes we all gathered. You’re not going to work on your own… Whatever you’re building, there must be a collective discussion: you prefer this, you prefer that… And when we had a cooperative meeting to make a decision together, obviously we all assembled.

In 1974, a milestone “special music issue” of L’Éducateur provided a good overview. It compiled key papers from former publications with contributions and feedback from members of the commission. As a written addendum to the records the ICEM was releasing back then, this issue confirms that the idea behind the recording of “free,” “concrete” or “electronic” music was not to make children mimic or learn by force the gestures and codes of avant-garde music, but to encourage their own personal forms of exploration and welcome the unpredictable.

As the creativity of pupils could give unexpected and sometimes puzzling results, the curiosity and open-mindedness of teachers were valuable allies, for they helped them question the limits of their own listening practices or aesthetic criteria:

JLM: I listened to music that was different from what we usually used in school. I loved jazz, and when free jazz and all that stuff came round in the sixties… I was into that. So, when the kids were making music, sometimes it just “clicked” in my head: “Hey, we’ve got something interesting here!”. Things like Stockhausen’s Stimmung, that was my stuff, but I also loved listening to Ella Fitzgerald (…). And if things took a more contemporary turn down there, in Vence, it was also because of the people gravitating around the school. Prévert had visited it, Michel-Edouard Bertrand was a friend of Freinet’s son in law, Jacques Bens, a co-founder of the OuLiPo… A certain amount of people from outside school took part in activities, and they were happy to sing with the kids or make them sing, imagine stories…

The tape-recorder in school

More technically speaking, as early as the 1960s, the progressive increase in classes equipped with portative tape-recorders became essential for the Mouvement.

Their wish to encourage the practice of amateur recording by giving access to suitable equipment can be seen as the equivalent, in the field of sound, of an older process initiated in the mid-1920s to develop printing in school. Indeed, for Freinet, classroom journals had always been ideal synthetic materials, for they involved a complete set of skills and crafts: reporting, editing, illustration, photography, typography, printing. In this context, enthusiast children could have a go at writing and publishing articles, chronicles, reports and drawings, which sometimes went with lyrics or scores. Not only were they in charge of contents, but they also controlled manufacturing and distribution.

JLM: For me, it was Raymond Dufour who got tape-recorders into schools, with wire recording. This was how he discovered child speech in its spontaneous form, whereas before that, speech was nearly entirely based on writing: things were written and read out loud, and the recordings were not so interesting, they were far more didactic. Firstly, because reading aloud is not that easy. And secondly, because it didn’t have much to do with the personal or family lives these children had […]. And then, Pierre Guérin happened to meet Gilbert Paris, who manufactured recorders, and from then on, much work was done in a more documentary perspective.

Indeed, intent on promoting and developing the use of the tape-recorder in school, Pierre Guérin supervised, in the early 1960s, the launch of the massive “BT Sonores” collection, a broad selection of audio sources, thematic conferences and classroom recordings with children from all countries and all social backgrounds speaking about their everyday lives, interests, ambitions, living conditions and existential questionings. The voices of great scientists such as Henri Laborit were compiled with group discussions between pupils dealing with topics as serious and diverse as death, unemployment, teenage anxieties, solar system exploration or daily life in Bora-Bora. While the function of music remained secondary, the collection showed the wish to revive a personal practice of documentary recording in tune with the philosophy embraced by another of Pierre Guérin’s collaborators, Jean Thévenot, a broadcaster reputed for his work at the RTF, especially with Chasseurs de sons, a radio programme meant to promote amateur recording.

In his 1965 conference, Célestin Freinet remarked that when he was making his debuts as an educationist, “no one believed that a small kid in nursery or elementary school could express, in written or oral form, a meaningful thought that was worth noting.” The Mouvement de l’École moderne relayed and championed the voices of childhood, and one of its most remarkable intuitions may have consisted in firmly believing that all these “songs showcased in wax” deserved publicity.

Phonographic pedagogy

Since 1928, the Mouvement had in the CEL (Coopérative de l’Enseignement Laïque) an independent structure that could conceive, direct, manufacture and distribute their many printed publications and the pedagogic material destined to Freinet classrooms.

As the notion of “phonographic pedagogy” (defending the record as a tool for musical education) began to emerge in France in the early 1930s, Freinet mentioned, in his correspondence with the world music lover and collector Charles Wolff, the idea of a traveling music library that could tour around schools, as did the bookmobile funded by the Musée de l’éducation.

To succour teachers, who often had difficulty having the classroom equipped, the CEL conceived its own robust and powerful phonograph, had it manufactured and put it for sale at a reasonable price. While the Mouvement de l’École moderne was going on its quest for “a new record-based technique for musical expression,” the CEL added record publishing to its activities, and its very first 78 rpm records for a “natural method for music initiation” appeared in the 1940s, with poetry and music by pupils from the Vence Freinet school as well as lines borrowed from Prévert and sung “in the vocal register of children,” to which were added, of course, the piano accompaniment facilitating practice, while the B side, entitled “la part du maître” (the master’s part), offered oral advice.

However, it was only in the early 1960s, when the Mouvement and the CEL apparently reached their cruising publishing speed, that a new series of more surprising records could come out. Available on subscription, recordings by the Club de la Bibliothèque sonore were the first ones to show a clear move in the practice of “Free music,” with the first truly completely improvised vocal and instrumental pieces, the first works exploiting the potential of the tape-recorder (pitch and reverse switch), and the first experiments with the Ariel.

At the start of the 1970s, a new step was taken in record publishing as the ICEM commission for music intensified its activities. Jean-Louis Maudrin wanted a sonic equivalent of La Gerbe, the “coorevue” (a neologism that could be translated as “coomag,” with coo for cooperative) which Freinet had launched in 1927, with children compiling their own texts and drawings in leaflets “composed and elaborated in school.”

JLM: We wanted quality, because there was sharing. When you share something, it cannot be anything! The various pieces were chosen by the pupils as the tape circulated from one class to another, in a predetermined “order.” Then we had to adapt the selection to the format: we had something like eight minutes. Not ten, not two! So, we had to make everything fit before sending the whole thing to Gilbert Paris, who built the recorders.

These new records were soon sent to subscribers as a supplement to Art Enfantin et Créations, a journal founded in 1959 by Élise Freinet, who globally devoted herself to promoting the artistic expression of children on both practical and theorical levels, following an intellectual path that is not unlike Jean Dubuffet’s with Art brut. Joint publication made it possible to detail in print, for each record, the context of production and a step-by-step approach.

JLM: Sometimes I added a discography, not only for masters to share it with pupils, but also to show that kids were not the only tinkerers. It was a way to normalise tinkering, and to incite people to educate their ears for once! Pierre Henry or Pierre Schaeffer could be heard on the radio.

Take the time to listen

This compilation therefore presents a selection of recordings from the thirty or so records released by the CEL between 1962 and 1982, partly deviating these sound archives from their original function to offer them to a new audience.

Recorded in Paul Delbasty’s classroom in Buzet-sur-Baise, the oldest pieces have been taken from a BT Sonore and several Club de la Bibliothèque Sonore records, which feature some of the first experiments with the Ariel. Different versions of the melody entitled “Une petite fleur” punctuate our track list like so many “variations on a theme.” Actually, ICEM records often adhered to this principle, as they insisted on presenting various research steps rather than the “final” outcome, or showing the way pupils declined another pupil’s work or idea. As far as we know, “Saturne” (also recorded in Buzet) was one of the first tape-recorder pieces to be based on the use of pitch and reversed reading in an educational context.

The other tracks have all been selected from the record series that the ICEM released in the 1970s. On the title track, the young Frédéric Chanu starts singing a bewildering ode to joy on a melancholy tone verging on detachment, making heavy clanks all the while. As for “The Ocean,” “C’était l’histoire” and other excerpts from L’Enfant de la liberté, they belong in the register of intimate folk, with songs recorded in secondary school (with twelve-to-eighteen-year-old kids), originally written as an exercise in French rather than in music.

Other pieces more directly resulted from experiments in “concrete” or “electronic” music, ranging from the rudimentary manipulations in “Voix, percussions ou cithare à l’envers” to the fragile balance reached in “Voix, larsen et percussions,” a set of sounds so minimal that one can still wonder at the existence of adults wise enough to consider them as musical expressions worth publishing. As Jean-Louis Maudrin remarked back then, in this elementary process “a single recorded noise can spark off hours of eternally renewed creation. It challenges aesthetic criteria, you cannot tell if what you hear is beautiful or not, if you like it or not. Children are faced with the unheard… a new world where nothing can make you fail.”

In a similar spirit, “Hiroshima” is actually the work of a junior high school pupil who, having received an amp as a Christmas present, plugged his electric guitar onto it and started playing something very different from any rock n’ roll standard: “I began with sound tests: Larsen effect, making noise with marbles and pinches, and then I had the idea to make something OK with all this. So, I recorded all my experiments and assembled them in a row. I didn’t add any sound after editing the tape. I was happy. It was an experiment with sounds. We listened to it in class and sent it to our penfriends in Vizille. They answered us and as I’d asked them for a title, they suggested “Hiroshima.” I listened to it once more and found the title relevant. I didn’t make any change.” In the end, it featured on so many ICEM records that it became one of its most often compiled tracks.

A small selection of a-capella tracks was also essential to remind the major part played by “free singing”, with voice as the “original instrument.” Offering an excerpt from “Recherches sur la voix” and the beautiful proto-punk babble-like glossolalia of “Français,” we invite the curious to complete this selection with a listening of the original records.

A few instrumental, percussive or modal tracks – some of which were originally destined to accompany theatrical dances (“Les Monstres”) – complete this overview, the poetry of which sometimes has a touch of the “nouvelle vague” (“Se glisser dans ton ombre”). It should be noted, to conclude, that another version of these pieces was actually the work of adults having adhered to a group of student teachers who had “no musical training whatsoever” and wanted to experiment as well.

Considered as a whole, this corpus remains in many ways strikingly singular. Firstly, because of the quantity published: if other schools occasionally released records that were stylistically close, the ICEM worked with a consistency that made their project truly extraordinary. Secondly, because this work was done ahead of its time: it was only in the mid-1970s that similar practices became more common in the state educational system. These unique archives document what music by and for children can or could be when the record is used as an object completely freed from the qualitative filters inherently structuring music industry.

Unfortunately, as Célestin Freinet died in 1966, he did not have the opportunity to appreciate all the musical developments that sprang from the joyful upheaval he caused. Such innovating practices are still defended in today’s ICEM by the work group Pratiques sonores et musicales, whose members engage in the task undertaken by their pioneering predecessors. Giving a detailed overview of the work done by the ICEM commission for music, an article recently published in Nouvel Éducateur emphasised how “exceptional all this was: nowhere else in the world was anything similar accomplished and carried on for three decades.” May this record testify to this work and contribute to the sharing of such treasures with a new generation of listeners.

Tape music, sound experiments and free folk songs by children from Freinet classes

1962-1982

France, early sixties: the Mouvement de l’École moderne is in full bloom. Relying on the experiments and writings of its founder, the educationist Célestin Freinet, this consortium of teachers is about to give empirical evidence proving that another approach to music in school can be fruitful, distancing itself from government directives.

With its pragmatic, anti-authoritarian tack, the method that Freinet was already developing in the 1920s held children in respect, giving them confidence and autonomy. In a Europe that was just beginning to recover from WWI, Freinet was working concomitantly with the historical burgeoning of active learning promoted by other great educationists such as Montessori in Italy, Decroly in Belgium or Ferrière in Switzerland, notably within the Ligue international pour l’Éducation nouvelle. Freinet very soon started to put his principles into practice, experimenting in person a series of innovating techniques that would become emblematic: removing the rostrum, reorganizing the classroom, encouraging cooperation, developing activities such as school printing or inter-school correspondence… And all this went with the publishing of documentation, files and specific teaching material by the Coopérative de l’Enseignement Laïc (the CEL, a cooperative for secular education).

A team of inspired associates quickly formed around Célestin and his wife, Élise. Intent on circulating ideas and perfecting methods, they also contributed to structuring a Mouvement that drew increasing attention. When the couple founded its emblematic alternative school in the small town of Vence, in 1934, the CEL was already counting more than three hundred members from sixty different territorial departments. At the dawn of the sixties, the Mouvement gathered a considerable number of teachers working in state schools, and even if they were far from constituting any kind of majority, they could be found throughout the national territory.

As the wish to encourage free expression was central in the Freinet philosophy, arts and crafts were given more importance at school; in this regard, singing and music had a part to play, just as much as writing or drawing. While classrooms filled with a joyful jumble of sound-making objects (springs, bottles and basins, dismantled piano frames, drums, bamboos and the first DIY electronics), singular forms of music started ringing out: wild improvising, delicate a-cappella singing, clanks and dissonant string hammerings, basic experiments with magnetic tapes, evanescent folk songs…

This approach might seem surprisingly ahead of its time, but what is even more astonishing is that physical traces of these experiments can still be accessed today. Between 1962 and 1982, recordings collected from schools everywhere around France were compiled on dozens of vinyl records. Mostly destined to teachers and friends supporting or gravitating around the Mouvement, these short-format records documented the evolution of practices and approaches: catchy headings such as “Musique libre” (free music), “Recherches sur la voix” (vocal experiments), “Musiques concrètes” (concrete music), “Musiques électroniques” (electronic music) or “Musiques d’ailleurs” (music from elsewhere) are particularly telling. And the music that could be heard on these groundbreaking records was the work of pupils from small towns in Lot-et-Garonne, Oise and Alpes Maritime – not exactly the archetypal privileged children benefitting from an upper-class economic and cultural background… Rather, children from rural schools with a single classroom, and sometimes, atypical or struggling children oriented towards the so-called “classes de perfectionnement.”

Free music

Within the Mouvement de l’École moderne, the importance attached to music, its recording and the record itself formed three interrelated topics, the history of which is that of a captivating collective adventure.

When Célestin Freinet sternly declared, during an educational lecture he was giving in 1965, that “the traditional teaching of music had gone bankrupt,” he was actually pointing out that groundwork for an alternative was already in progress. Since the 1930s, the Mouvement’s quest for a “natural method for music initiation” had been adapting the principles of Freinet’s “natural method” for reading skills acquisition. A whole pedagogy grounded in interdisciplinary key notions was imagined, and as always with Freinet, the starting point was practice rather than rule. Dynamic and pragmatic, it encouraged the child’s natural empirical approach, hoping to liberate them from the fear of failure, stimulate their desire for learning and deeply enroot theoretic knowledge in concrete intimate experience. Far from contentedly praising spontaneity, laxness and first drafts, the notion of “enquiry-based learning” claimed equal respect for the various paths that pupils took and considered them able to adopt their own structured approach.

This had many implications for the teaching of arts. The very notion of repertoire gave way to freedom of personal expression as a major value. Instead of trying to have pupils clumsily copy a model, teachers encouraged an intimate experience of production, following Goethe’s maxim according to which children cannot be sensitive to art works unless they have created something themselves. Whether modest or grandiose, the creation was attributed to the child, now considered as an author able to define the intention, the form and the modalities of their work.

In the pre-war issues of L’Éducateur prolétarien, several institutors – sometimes working in close collaboration with Freinet, as Roger Lallemand did – regularly shared their thoughts on the teaching of music at school. Their articles could equally deal with singing as a free practice, the place of pipes or percussion instruments, composition, or the formation and staging of small children orchestras. Clearly aware of the progress that was being made abroad, these contributors also referred to pioneering books and works by the American educationist Satis Coleman or the French one Lina Roth.

When the Institut Coopératif de l’École Moderne (ICEM) was founded in 1947, other teachers and key figures of the Mouvement progressively took the helm. In the second half of the 1950s, Maurice Beaugrand or Paul Delbasty suggested new directions in “free music,” which was then practiced in school as “free writing” or “free drawing” were. In 1957 a special issue of La Bibliothèque de travail directed by Delbasty suggested to begin at the beginning by radically questioning lute-making and the instrumentarium as determining factors in the practice of music and the very form it can take. Taking into account a budgeting that made it difficult for an entire class to be equipped, this issue detailed a whole series of practical solutions to facilitate the building of instruments through recycling: cookware lids, tins of paint, bottles making a xylophone or anything that could be somehow used as a pipe. Cheap and demystified, the instrument was adapted to the height and skills of children: it became both affordable and accessible. A small zither made with a tin of sardines and a bigger one built with a wooden box also heralded the conception of the Ariel, a plucked string instrument that could be easily built and intuitively tuned, and which would become emblematic of the music produced in Freinet classes.

In another BT issue published in 1959, G. Jaegly and C. Pons presented a series of small sound experiments: building other rudimentary instruments, amplifying a vinyl groove with a paper cone, visualising Chladni figures (geometrical patterns that can be observed on a vibrating plate covered with sand). In 1965, in a more theoretical spirit, Freinet and Delbasty drew up a very positive report surveying the work in progress and published it in L’Éducateur, n° 10. Beyond print, these ideas and techniques were promoted through training courses, symposiums and congresses regularly scheduled by the Mouvement.

At the end of the 1960s, research on musical practice began to be carried out, notably, by the “Commission musique,” a group of teachers particularly concerned with these issues. The names of Jean-Pierre Lignon, Paul Le Bohec or Jean-Jacques Charbonnier frequently appeared, along with that of Jean-Louis Maudrin, who coordinated the commission’s work and was one of its major members until 1978:

JLM: We didn’t want everything to be based on music, it was not the goal of the operation. I was interested in offering something to pupils. We wanted children to find out, invent, be included in the teaching process. With productions that were theirs, or others’, never mind. If you want schooling to work, children must be involved, and what can we do to involve them? Music, sculpture, photography… We all intervened in turns, but the goal of the operation was to generate enthusiasm in everyone. And to be honest, it is far from being a piece of cake, because you have to do with what you get. If you want to make instruments, is there enough room for construction anywhere in the class? It was a recurrent problem, especially in big city schools.

Respecting the autonomy, creativity and rhythm of each child, activities were also systematically envisaged as something to be shared with the whole class and penfriends in distant schools, to whom recordings were sent.

JLM: Sometimes the class was totally split up, sometimes we all gathered. You’re not going to work on your own… Whatever you’re building, there must be a collective discussion: you prefer this, you prefer that… And when we had a cooperative meeting to make a decision together, obviously we all assembled.

In 1974, a milestone “special music issue” of L’Éducateur provided a good overview. It compiled key papers from former publications with contributions and feedback from members of the commission. As a written addendum to the records the ICEM was releasing back then, this issue confirms that the idea behind the recording of “free,” “concrete” or “electronic” music was not to make children mimic or learn by force the gestures and codes of avant-garde music, but to encourage their own personal forms of exploration and welcome the unpredictable.

As the creativity of pupils could give unexpected and sometimes puzzling results, the curiosity and open-mindedness of teachers were valuable allies, for they helped them question the limits of their own listening practices or aesthetic criteria:

JLM: I listened to music that was different from what we usually used in school. I loved jazz, and when free jazz and all that stuff came round in the sixties… I was into that. So, when the kids were making music, sometimes it just “clicked” in my head: “Hey, we’ve got something interesting here!”. Things like Stockhausen’s Stimmung, that was my stuff, but I also loved listening to Ella Fitzgerald (…). And if things took a more contemporary turn down there, in Vence, it was also because of the people gravitating around the school. Prévert had visited it, Michel-Edouard Bertrand was a friend of Freinet’s son in law, Jacques Bens, a co-founder of the OuLiPo… A certain amount of people from outside school took part in activities, and they were happy to sing with the kids or make them sing, imagine stories…

The tape-recorder in school

More technically speaking, as early as the 1960s, the progressive increase in classes equipped with portative tape-recorders became essential for the Mouvement.

Their wish to encourage the practice of amateur recording by giving access to suitable equipment can be seen as the equivalent, in the field of sound, of an older process initiated in the mid-1920s to develop printing in school. Indeed, for Freinet, classroom journals had always been ideal synthetic materials, for they involved a complete set of skills and crafts: reporting, editing, illustration, photography, typography, printing. In this context, enthusiast children could have a go at writing and publishing articles, chronicles, reports and drawings, which sometimes went with lyrics or scores. Not only were they in charge of contents, but they also controlled manufacturing and distribution.

JLM: For me, it was Raymond Dufour who got tape-recorders into schools, with wire recording. This was how he discovered child speech in its spontaneous form, whereas before that, speech was nearly entirely based on writing: things were written and read out loud, and the recordings were not so interesting, they were far more didactic. Firstly, because reading aloud is not that easy. And secondly, because it didn’t have much to do with the personal or family lives these children had […]. And then, Pierre Guérin happened to meet Gilbert Paris, who manufactured recorders, and from then on, much work was done in a more documentary perspective.

Indeed, intent on promoting and developing the use of the tape-recorder in school, Pierre Guérin supervised, in the early 1960s, the launch of the massive “BT Sonores” collection, a broad selection of audio sources, thematic conferences and classroom recordings with children from all countries and all social backgrounds speaking about their everyday lives, interests, ambitions, living conditions and existential questionings. The voices of great scientists such as Henri Laborit were compiled with group discussions between pupils dealing with topics as serious and diverse as death, unemployment, teenage anxieties, solar system exploration or daily life in Bora-Bora. While the function of music remained secondary, the collection showed the wish to revive a personal practice of documentary recording in tune with the philosophy embraced by another of Pierre Guérin’s collaborators, Jean Thévenot, a broadcaster reputed for his work at the RTF, especially with Chasseurs de sons, a radio programme meant to promote amateur recording.

In his 1965 conference, Célestin Freinet remarked that when he was making his debuts as an educationist, “no one believed that a small kid in nursery or elementary school could express, in written or oral form, a meaningful thought that was worth noting.” The Mouvement de l’École moderne relayed and championed the voices of childhood, and one of its most remarkable intuitions may have consisted in firmly believing that all these “songs showcased in wax” deserved publicity.

Phonographic pedagogy

Since 1928, the Mouvement had in the CEL (Coopérative de l’Enseignement Laïque) an independent structure that could conceive, direct, manufacture and distribute their many printed publications and the pedagogic material destined to Freinet classrooms.

As the notion of “phonographic pedagogy” (defending the record as a tool for musical education) began to emerge in France in the early 1930s, Freinet mentioned, in his correspondence with the world music lover and collector Charles Wolff, the idea of a traveling music library that could tour around schools, as did the bookmobile funded by the Musée de l’éducation.

To succour teachers, who often had difficulty having the classroom equipped, the CEL conceived its own robust and powerful phonograph, had it manufactured and put it for sale at a reasonable price. While the Mouvement de l’École moderne was going on its quest for “a new record-based technique for musical expression,” the CEL added record publishing to its activities, and its very first 78 rpm records for a “natural method for music initiation” appeared in the 1940s, with poetry and music by pupils from the Vence Freinet school as well as lines borrowed from Prévert and sung “in the vocal register of children,” to which were added, of course, the piano accompaniment facilitating practice, while the B side, entitled “la part du maître” (the master’s part), offered oral advice.

However, it was only in the early 1960s, when the Mouvement and the CEL apparently reached their cruising publishing speed, that a new series of more surprising records could come out. Available on subscription, recordings by the Club de la Bibliothèque sonore were the first ones to show a clear move in the practice of “Free music,” with the first truly completely improvised vocal and instrumental pieces, the first works exploiting the potential of the tape-recorder (pitch and reverse switch), and the first experiments with the Ariel.

At the start of the 1970s, a new step was taken in record publishing as the ICEM commission for music intensified its activities. Jean-Louis Maudrin wanted a sonic equivalent of La Gerbe, the “coorevue” (a neologism that could be translated as “coomag,” with coo for cooperative) which Freinet had launched in 1927, with children compiling their own texts and drawings in leaflets “composed and elaborated in school.”

JLM: We wanted quality, because there was sharing. When you share something, it cannot be anything! The various pieces were chosen by the pupils as the tape circulated from one class to another, in a predetermined “order.” Then we had to adapt the selection to the format: we had something like eight minutes. Not ten, not two! So, we had to make everything fit before sending the whole thing to Gilbert Paris, who built the recorders.

These new records were soon sent to subscribers as a supplement to Art Enfantin et Créations, a journal founded in 1959 by Élise Freinet, who globally devoted herself to promoting the artistic expression of children on both practical and theorical levels, following an intellectual path that is not unlike Jean Dubuffet’s with Art brut. Joint publication made it possible to detail in print, for each record, the context of production and a step-by-step approach.

JLM: Sometimes I added a discography, not only for masters to share it with pupils, but also to show that kids were not the only tinkerers. It was a way to normalise tinkering, and to incite people to educate their ears for once! Pierre Henry or Pierre Schaeffer could be heard on the radio.

Take the time to listen

This compilation therefore presents a selection of recordings from the thirty or so records released by the CEL between 1962 and 1982, partly deviating these sound archives from their original function to offer them to a new audience.

Recorded in Paul Delbasty’s classroom in Buzet-sur-Baise, the oldest pieces have been taken from a BT Sonore and several Club de la Bibliothèque Sonore records, which feature some of the first experiments with the Ariel. Different versions of the melody entitled “Une petite fleur” punctuate our track list like so many “variations on a theme.” Actually, ICEM records often adhered to this principle, as they insisted on presenting various research steps rather than the “final” outcome, or showing the way pupils declined another pupil’s work or idea. As far as we know, “Saturne” (also recorded in Buzet) was one of the first tape-recorder pieces to be based on the use of pitch and reversed reading in an educational context.

The other tracks have all been selected from the record series that the ICEM released in the 1970s. On the title track, the young Frédéric Chanu starts singing a bewildering ode to joy on a melancholy tone verging on detachment, making heavy clanks all the while. As for “The Ocean,” “C’était l’histoire” and other excerpts from L’Enfant de la liberté, they belong in the register of intimate folk, with songs recorded in secondary school (with twelve-to-eighteen-year-old kids), originally written as an exercise in French rather than in music.

Other pieces more directly resulted from experiments in “concrete” or “electronic” music, ranging from the rudimentary manipulations in “Voix, percussions ou cithare à l’envers” to the fragile balance reached in “Voix, larsen et percussions,” a set of sounds so minimal that one can still wonder at the existence of adults wise enough to consider them as musical expressions worth publishing. As Jean-Louis Maudrin remarked back then, in this elementary process “a single recorded noise can spark off hours of eternally renewed creation. It challenges aesthetic criteria, you cannot tell if what you hear is beautiful or not, if you like it or not. Children are faced with the unheard… a new world where nothing can make you fail.”

In a similar spirit, “Hiroshima” is actually the work of a junior high school pupil who, having received an amp as a Christmas present, plugged his electric guitar onto it and started playing something very different from any rock n’ roll standard: “I began with sound tests: Larsen effect, making noise with marbles and pinches, and then I had the idea to make something OK with all this. So, I recorded all my experiments and assembled them in a row. I didn’t add any sound after editing the tape. I was happy. It was an experiment with sounds. We listened to it in class and sent it to our penfriends in Vizille. They answered us and as I’d asked them for a title, they suggested “Hiroshima.” I listened to it once more and found the title relevant. I didn’t make any change.” In the end, it featured on so many ICEM records that it became one of its most often compiled tracks.

A small selection of a-capella tracks was also essential to remind the major part played by “free singing”, with voice as the “original instrument.” Offering an excerpt from “Recherches sur la voix” and the beautiful proto-punk babble-like glossolalia of “Français,” we invite the curious to complete this selection with a listening of the original records.

A few instrumental, percussive or modal tracks – some of which were originally destined to accompany theatrical dances (“Les Monstres”) – complete this overview, the poetry of which sometimes has a touch of the “nouvelle vague” (“Se glisser dans ton ombre”). It should be noted, to conclude, that another version of these pieces was actually the work of adults having adhered to a group of student teachers who had “no musical training whatsoever” and wanted to experiment as well.

Considered as a whole, this corpus remains in many ways strikingly singular. Firstly, because of the quantity published: if other schools occasionally released records that were stylistically close, the ICEM worked with a consistency that made their project truly extraordinary. Secondly, because this work was done ahead of its time: it was only in the mid-1970s that similar practices became more common in the state educational system. These unique archives document what music by and for children can or could be when the record is used as an object completely freed from the qualitative filters inherently structuring music industry.

Unfortunately, as Célestin Freinet died in 1966, he did not have the opportunity to appreciate all the musical developments that sprang from the joyful upheaval he caused. Such innovating practices are still defended in today’s ICEM by the work group Pratiques sonores et musicales, whose members engage in the task undertaken by their pioneering predecessors. Giving a detailed overview of the work done by the ICEM commission for music, an article recently published in Nouvel Éducateur emphasised how “exceptional all this was: nowhere else in the world was anything similar accomplished and carried on for three decades.” May this record testify to this work and contribute to the sharing of such treasures with a new generation of listeners.